C. E. Chaffin

Coyote

In heaven where dandelions

are always blooming

and the bumblebee’s sting is a tonic,

normal weight is not a requirement

and smoking is allowed.

Why should a god care about such things?

Still we come with our litany

of long-deliberated injustices

dressed for the big interview,

Florsheims polished

affable but not obsequious

(“I like the cut of your jib”)

only to discover the personnel director

is a clown with a bulbous nose

and goofy checkered slippers

slurping a rainbow pop

to match his wig.

“Gee willikers!” he says

to all the moral imperatives

that propelled us there

And all the king’s horses

and all the king’s men

When I was a boy

I saw God in the forest

or rather through the forest

before the agents of the clown

put a Lutheran crown on me.

Oh black Sundays! Black hymnals

and black-suited pastor

beneath the high darkness

of a peaked, beamed ceiling;

songs of armies and angels

in a benediction of dust motes,

the church triumphant,

the church hypoxic,

God-in-a-Box!

How I hated the wool trousers

against my sunburned legs

and the oppressive whispers of parishioners

as I squirmed like a snake

in the smooth pew.

I wanted Dionysus to dance

down the aisle like David,

praising God from his diaphragm,

splashing wine on all the saints

imprisoned in glass hagiography,

the poor cartoons.

Oh Clown-God, Coyote-God,

did you ever hide yourself in hymnals?

We must come to laugh

at all your disguises.

~

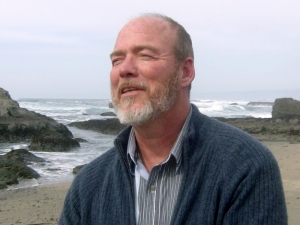

Reflection

See mine, in the window there,

beard quilled in white?

Above, a vast forehead like a desert

as if the skull were pushing through?

Right, a scar from cops’ batons

extends my eyebrow, and my mustache

has been split by a brass knuckle.

The right eye’s green, the left blue

with crow’s feet spread out

like shatter-proof glass shattered,

then all the luggage below, harvest

of late nights drinking.

Nose, flat and aboriginal,

strong even teeth but yellowed

by smoke and coffee, wide smile,

full lips upcurling at the corners.

Laugh lines outnumber other furrows

though puzzlement grooves much.

Not a rich man’s face, it lacks

a certain earthly satisfaction

but I hope it’s free from envy.

II

The poor you have with you always,

the rich man can’t help but rub it in,

his mere existence fathers discontent

which powers ambition

which feeds achievement

which seeks comparisons

which breed dissatisfaction,

giving birth to envy.

It’s not the thorn against the rose

but both against the deer;

the deer makes them equals

and the sun, confederates.

III

On and on the human engine runs

toward the swimming pool

purchased on credit

from a second mortgage,

toward the notion

that having all

might cure not having all.

On we fly like wasps

disturbed by a lawnmower,

no furies needed

but our lusts.

The ouroboros of desire

is lugubriously predictable.

How much is that Buddha in the window?

~

For Sergio

I took my Dick Tracy decoder ring

and watched the Milky Way track

slowly across the limpid night

from north-south to east-west

like a great sparkling barge

heaving 90 degrees

in a plodding Mississippi turn

and I marveled at the sight

like the shepherds, I suppose.

I took my Dick Tracy decoder ring

and placed it on my navel, as poets do

until the network of my extended consciousness

wove itself through every organ

in a web of simple, exploratory axons–

as in the giant squid, whose signal conduction

is easiest to study, whereas

the complexity of human neurons,

not to mention their relative miniaturization,

makes decoding more problematic–

(this bird-walk demonstrates

how poets lose control of their intentions).

I took my Dick Tracy decoder ring

and placed it on a new translation of Neruda

by William Daly, and wondered

how one mind could generate

so many tropes so fucking effortlessly

while I ground out my metaphors

with a mortar and pestle

in the noonday sun on equatorial Venus.

What must it be like to be so gifted,

to virtually think in metaphor?

I couldn’t imagine.

I took my Dick Tracy decoder ring

and held it up to you, Dear Reader,

wondering what sort of tripe

you next expected from my pen,

what nonsense you might endure

and what truth you may not

and with a dash of Coyote

I wondered how to pose

the usual questions in a novel way, as in:

“Why does this blue toaster

sport yellow ribbons

when you know very well

they could catch fire or else melt?”

Yet I found this insufficient

for the Post-Modern void,

so I grabbed a neon-pink dildo

and waved it at the new moon,

hoping for an erection in two weeks

while contenting myself, like Jim Morrison,

to masturbate in public and call it poetry.

Lastly I turned my Dick Tracy decoder ring

to God Almighty, seeking to deduce

however how and whatever

what and whyever why and who

made this whole thing up and what

did the Devil have to do with it

and where is he now and why do I ask

such questions of an Invisible Spirit

who likely cannot relate to something

so fiercely limited as a human?–

when I remembered 5:30 Mass

and went to eat my words

become his Word again.

~

Deal?

I wanted a mind

not like a steel trap

but a platinum guillotine

the way my father taught me,

how to stick it to the sucker like a needle in the eye,

how to puncture the white underbelly of his pride

with a samurai ritual knife, how to disembowel

and afterwards stuff his own entrails with his flesh

and feed him to himself as sausage, sausage,

feed him to himself as sausage.

Early I learned

how to cut human pride

with a buzz saw in my hands

sawing away pretensions

to nobility without connection,

intent to expose the rotten infrastructure

of the Beast and its functionaries:

tie-wearers, thralls, desk jockeys

who think they rule the world

like little Napoleons

watching one administration come

and another go

content in their G status

and the pension and wife and fireplace

and dog and braided rug

like a picture in Home and Garden

don’t ya know, don’t ya know?

I learned long ago

how to divide the corpse

into equal portions and arrange the corpse beetles

for parade in their velveteen tights–

three pair each, the nimble six-footed dancers.

And come the shiny cockroaches!

But I digress.

I was fessing to my tendency,

learned from my father,

to skewer others emotionally

for entertainment’s sake

though I have tried to turn

this gift to therapeutic uses with some success

but many complaints, to be honest.

Humankind cannot bear very much reality.

Why wouldn’t I be honest?

(Who reads poetry anyway?)

If I go slicing around

not caring whom I wound,

remember that I do it for the general weal

bent on one thing: to slice the faux flesh

from the living, to rescue the eternal

from the temporal curse,

that thorn in the proverbial paw

of the proverbial God sacrificed to man.

Come, Lord Jesus.

It is the only hope for our blindness.

I see miracles every hour and the world says I’m crazy,

that I’m manic, that I suffer from messianic delusions.

What if they’re not delusions?

I don’t think they are!

Hoo hoo! Ha ha!

I promise, Lord, if you come

I will no longer wound my fellows

with this vicious tongue of mine.

I will not do soul-surgery in public

where we can watch them bleed.

I promise to be nicer,

to be more like Jesus,

more like you.

Deal?

~

Failure of Evasion

You tore my heart out again,

right through my mouth

like an apple launched by a slingshot.

“Slingblade,” that movie about

the mentally ill avenger

played by Angelina Jolie’s first husband

the one she got tattoos with, ya know?

Where the rumor was they wore

vials of each other’s blood

around their necks?

Sick stuff, huh?

You can’t help but read the tabloids.

Jon Voight and Angelina

got some unfinished business

I’d guess, and just look at their lips,

the same fucking lucious lips,

a DNA bonus for nothing, a gift.

* * *

Author’s commentary: When Sam invited me to add a commentary to these poems, it seemed a little unfair, like Tom Sawyer peeking in at his own funeral. By its very nature poetry demands that an audience interpret it, or equally, it ought to be self-interpreting (if not self-evident).

These poems were written in the span of over a year. The first, “Coyote,” was written in August 2009 and finalized in December 2009. “Reflection” was written in September 2009 and the final draft in April 2010–if there is anything like a final draft. As Robert Lowell said, “No work of art is ever finished, only abandoned.” In fact, whenever I come across an old poem of mine, the temptation to revise is almost irresistible–and often unedifying, down to the last minute when I mail the proof back to the editor. Still, the impossible pursuit of perfection is not confined to Lexus.

The last three poems, “For Sergio,” “Deal,” and “Failure of Evasion” were written close together in the fall of 2010 and finalized rather quickly, in a matter of days. I was working fast then for reasons I’ll explain below.

Fellini said “All art is autobiographical” (which makes me wonder if he stole bicycles). In my case another element intrudes; like 20% of all poets, according to Kay Jamison’s “Touched with Fire,” I suffer from manic-depression. This disorder was endemic in both the Romantics and the Confessionalists. Here’s a list: Byron, Shelley, Keats, Coleridge and possibly Blake; Lowell, Roethke, Plath, Jarrell, Berryman and possibly Sexton. At the least these are interesting historic clusters, though very possibly explained not by cultural antecedents but random statistical concentrations. According to Dr. Jamison, more poets suffer from manic-depression than practitioners of any other art, hands down (or up, as the case may be). She happens to share the disorder. Put simply, the last three poems of this feature were written when I was in a manic state and thus written and finished quickly.

Before her suicide Plath wrote nearly a poem a day for over a month, a swan song of mania before the crash of depression that took her life. What’s amazing about her final output is the quality of the work. Whether delusional or not, she was working in a frenzy of creativity akin to Handel’s composing the Messiah in three weeks (when he took only tea and toast and hardly slept, raising suspicions that he, too, may have qualified for the diagnosis).

Do not think, however, that there is necessarily a relationship between artistic quality and manic-depression: there are plenty of bad bipolar artists. But if one has practiced his craft sufficiently, the energy that mania brings to an artist is nearly supernatural, and allows for major output in minimum time. When I was manic in the latter half of 2010, my poetry seemed to progress until I was beyond poetry—ultimately it seemed so easy to write that I came to devalue the art, especially as in my altered state I knew that, try as I might, it could never quite achieve the ineffable I so madly sought. Since then I have hardly written a line, primarily because a serious depression ensued in January of 2011, always inevitable after a mania.

As a physician I know of no worse disease than depression, and bipolar depression is by clinical consent the worst and most treatment-resistant form of it. I am only now recovering, and that stutteringly.

This confession has more to do with the production of the poems than their content, though the loosening of associations in the last three poems is more pronounced, a consequence of mania. Yet isn’t that what poets seek? To loosen the boundaries of language, to see the world in a grain of sand, to make shocking and unexpected connections, to force language to a new level? Great poetry does that, and practiced poets who are manic-depressive may have an advantage for this reason in a hypomanic state, which precedes mania, whereas advanced mania pretty much prevents the coherent production of verse. It’s a fine line and I’ve crossed it, usually in handcuffs before involuntary incarceration.

Despite the unstable mentality of the author, the chief theme of the first four poems is that of spiritual conflict and resolution. I have been religious more or less since my teens, though because of my inherited disorder my personal theology has suffered major distortions, and trying to work out the relationship of the self to self and to God has always been a major concern of my work. I suppose I could be justly labeled a metaphysical poet. Thus my disease more influences the style than the theme of these works, though the three written in mania have a certain bald power I can’t usually attain, and their loosening of associations, particularly in “For Sergio,” are heightened.

“Reflection” and “Coyote” were written in my usual fashion, working from a rough draft over time until I was satisfied. During their composition my mood was relatively normal, which in my last five years has been more the exception than the rule, though sadly dominated by depression, wherein I am forced to embrace formal verse, as I need a structure on which to hang my withering self. In any case, for me, manias are rare: I have suffered only three manic psychotic breaks in my adult lifetime, compared with 12 major depressions.

“Coyote” riffs off a recurrent consideration in my verse of God as the cosmic joker. Here are some lines from a much earlier poem, “Jawbreaker”:

God is beyond

these blistering hands

strapped to my sides

like plucked wings– either

an intergalactic sadist or a cosmic jester

chortling beneath his lapel of stars.

(A Small Garlic Press, published 3/99)

In Native American culture Coyote is identified as the trickster, like Loki or Merlin, playing a game at a level above us. In my best moments I want to agree that life is a good joke and the joke is on us, and that everything will be explained in the afterlife for the good; that suffering is redemptive and the gamble was worth it. In my worst moments I feel as if God were a mad vivisectionist and we but a ghastly experiment. The autobiographical passages in the poem hark back to my Lutheran upbringing. To say any more about the poem would be to intrude on the reader.

“Reflection” is the only example of an attempted self-portrait I can recall, and I think it began with my catching my reflection in the window in front of my computer one morning. From there the poem grew organically into a spiritual question, much like “Coyote,” though its positing is more comical. The second section of the poem is likely the most difficult, propelled by the last lines of the first, a hope that the speaker’s face is free from envy. Envy is the essence of narcissism, the wish to be acknowledged above another without regard to merit, based solely on the need of the psyche to elevate itself while diminishing others. Cain killed Abel out of envy; Joseph’s brothers left him for dead out of envy; Satan left heaven out of envy. Envy is not uncommonly the engine of murder. The last four lines of the section suggest a somewhat paradoxical antidote for this spiritual malady, and the trope may be somewhat difficult to assimilate, but I think it works. The final section, save for the last line, takes on a darker cast but should be self-explanatory.

“For Sergio,” like “Deal,” landed pretty much full-born on the page for reasons explained above. Where the decoder ring mantra came from I can’t say, but it served as a scaffolding for speculations about poets, readers and God, the reader taking the worst of it. The direct address to the reader is an antiquated and theatrical device, I admit, and I rarely use it. Yet here, as if the reader were coasting through the rest of the work, I felt a need to grab him by the collar and shake. One reason I am hard on poetry in this passage is because the tangible rewards of publishing poetry are so few that a little bitterness obtrudes—or perhaps not a little! The last stanza returns to the God problem, and the solution is fittingly irrational—one of experience, not reason.

“Deal” is more autobiographical than the previous poems, and more savage besides, as it obviously concerns Oedipal problems with my father and, subsequently, God, a clichéd theme if ever there was one, though I hope it a fresh treatment. I did have a mean, manic-depressive drunk of a father who committed suicide at 62 and did great damage to me and my siblings while alive. It may be one reason I took up the specialty of psychiatry, referred to in stanza IV, seeking to use his example of psychic intuition not to damage others and exalt myself, as my father did, but to heal them–though in the poem the speaker doubts such efforts. In stanza VI the speaker tries to explain and justify such confrontational methods because the stakes are so high: “I do it for the general weal /…/ to rescue the eternal / from the temporal curse.”

Stanza VI abandons such hopes and appeals directly to God, while admitting to accusations that the speaker may be deluded. Here the edge of sanity is very thin if present at all. (Manics typically suffer from messianic delusions, or at the very least think they have merged with the Divine in some unique and supernatural way.) Stanza VII essentially boils down the poem to a deal: That if Christ comes, the speaker won’t carry on the sins of his father. Yet this close reveals in the speaker a childish conception of Christ, that he was “nice” when he was anything but. With the Pharisees he could be excoriating; he could scent out false pride like a bloodhound and crush it in his jaws. So the speaker’s promise misses the point, first because his repentance depends upon Christ’s physical return, which obviates the point of religion, as it should not depend on deus ex machine but faith, and second, because the speaker is deluded into thinking he can actually cut a deal with God, Job’s error. Sorry, no deal. God’s first attribute is sovereignty, and he certainly can’t be blackmailed into hastening Christ’s return just to make one soul desist from his destructive tendencies. I hope in saying this I have not given away too much of the poem.

“Failure of Evasion” is the most directly autobiographical of the poems in emotion, though not in substance, save for the opening lines. Because of my florid mania my wife, whom I dearly love, left me on October 13, 2010, to preserve herself as I was obviously out of control by then. The pain of that abandonment is captured in the opening stanza. What follows is an attempt to change the subject, leaping directly to the memory of a movie—only to muse on the relationship of Billy Bob Thornton and Angelina Jolie, an intense relationship if ever there was one, ostensibly based on true and abiding love that was later lost. This proves that the unconscious returns to the pain no matter how far the conscious mind tries to evade it.

So there you have it, the wizard behind the curtain partly revealed.

What I most seek in my poetry is power, the power to grab the reader by the throat–so that even if he does not like the poem he is forced to finish it! I try not to shout but seduce, but if seduction fails I am not adverse to rape, as it were. And of course, in speaking to the reader about spiritual matters I also admonish myself.

How much mania changed my poetic voice the reader must decide, but I think the last three examples do not diverge too much from my style, marking more an elevation in intensity than a change in method.

8/9/11

Pingback: New at Blue Fifth Review / Poet Special Issue, featuring works by CE Chaffin « sam of the ten thousand things

Pingback: Whatever Comes Is Welcome « Walter Kitty's Diary

Pingback: 2011 – All Blue Five Notebook Issues, Special Issues, Features, Quarterlies, and Broadsides | Blue Fifth Review: Blue Five Notebook Series